This week my independent study project art embody has led me to discover the era of the post-impressionists, an artistic era that launched near the end of the 1880s.

The post-impressionist movement built off of the Impressionism's emphasis on the artist's individual interpretation or 'impression' of the subject matter. This movement, rather a non-unified group of artists pursuing their individual style, explored art's potentional as a vehicle for communicating emotion. With Cezanne, Gaughin and Van Gogh amoung their ranks these boundary-pushers boasted a diverse aesthetic that was decidedly distinct from the pastel luminescence of the impressionists. While the impressionist movement focused on naturalistically commiting fleeting light to canvas, the post-impressionists delved into the symbolic potentional of artwork. Post-impressionist works often have simplified forms and flat planes of clearly-defined color — aspects that apply directly to the varied ways in which they rendered the human figure.

Still inspired by last week's exploration of impressionism, I continued to sketch 'en plein air this week'. Here are a few sketches, the results of me planting myself in Luxembourg Gardens for a good while, stalking both carefree Parisians and the regal statues that sprinkle the park.

I also did a bit of 'impressionist' sketching in ink and charcoal on the beaches of Mallorca Island where I spent spring break:

To examine closely the myriad ways in which the diverse post-impressionist artists rendered the human figure, I headed back to the Musee D'Orsay. Embracing my inner tourist, here is a pic of me and my buddy Denise in front of the iconic museum clock. Time flies when you're creating art!

Wanting to commit more than just my mere 'impression' of the artwork to my sketchbook, I sat down with this statue of Hercules for a while and worked on transcribing the musculature.

The museum did not allow me to photograph post-impressionist works myself, so the following photos are taken from the web. I selected the following d'Orsay works to illustrate my main findings in terms of how the post-impressionists portrayed the human figure.

This first work is title 'Potrait de Madame M,' and was painted by Henri Rousseau in 1890. The clearly-defined planes of color and precise rendering of detail are in stark contrast to last week's Impressionist works. The hands are planar and monotone, while the face borders on caricature with it's elongated eyebrows and small mounds for nostrils. The figure appears sculpted; Rousseau's depiction careful and calculated. Anatomy is foregone for artistic style as the hands are deformed and the facial proportions are out of whack. This piece bears an eerie quality and delves into the realm of the symbolic, as underlined by it's mystery-soaked title featuring the illusive Madame 'M'.

Paul Serusier's 1891 'La Lutte Bretonne' also encapsulates several general principles of the post-impressionist era. The figures are dynamic and interesting, yet hold little semblance to realistic anatomy. For example, the feet and hands are much too large compared to the rest of the boys' bodies. Movement is created through the interwoven planes of color. Shading is accomplished for the most part through line, rather than the traditional gradient. In sum, color and shape take precedence over anatomy in this work by Serusier.

A similar subjugation of anatomy for creative expression of artistic style is exemplified by Vincent Van Gogh's 1889 piece below, 'LeMeridienne'. In this work the figures become inextricably tied to their context — the human forms and the background meld into a unified whole. The figures embody notions of fatigue and calm, and as they sink into the earth it is clear that the emotional punch, rather than accurate anatomy, is the focus here. The faces are indistinct, yet the bold brushstrokes delineate the contours of the bodies. Van Gogh is clearly more interested in the play of light, or the physical nature of the paint on the canvas, rather than anatomy.

'Et l'or de leur Corps,' is a 1901 post-impressionist Paul Gaughin work bearing similar qualities. The title, translated to 'And gold of their bodies', gives away the fact that color is Gaughin's primary focus in this work. The figures are outlined in black but the forms are described by clearly defined planes of brown, tan and orange. The figures are simplified and resemble modeled clay, the hands and fingers not clearly defined. The overall ambiance of the painting is seductive, calm, exotic and intimate. The painting has the atmosphere of having been painted from life, and from the paw-like nature of the right hand of the figure to the left, it was the color and atmosphere of the scene, rather than anatomy, that most struck Gaughin as he produced this work.

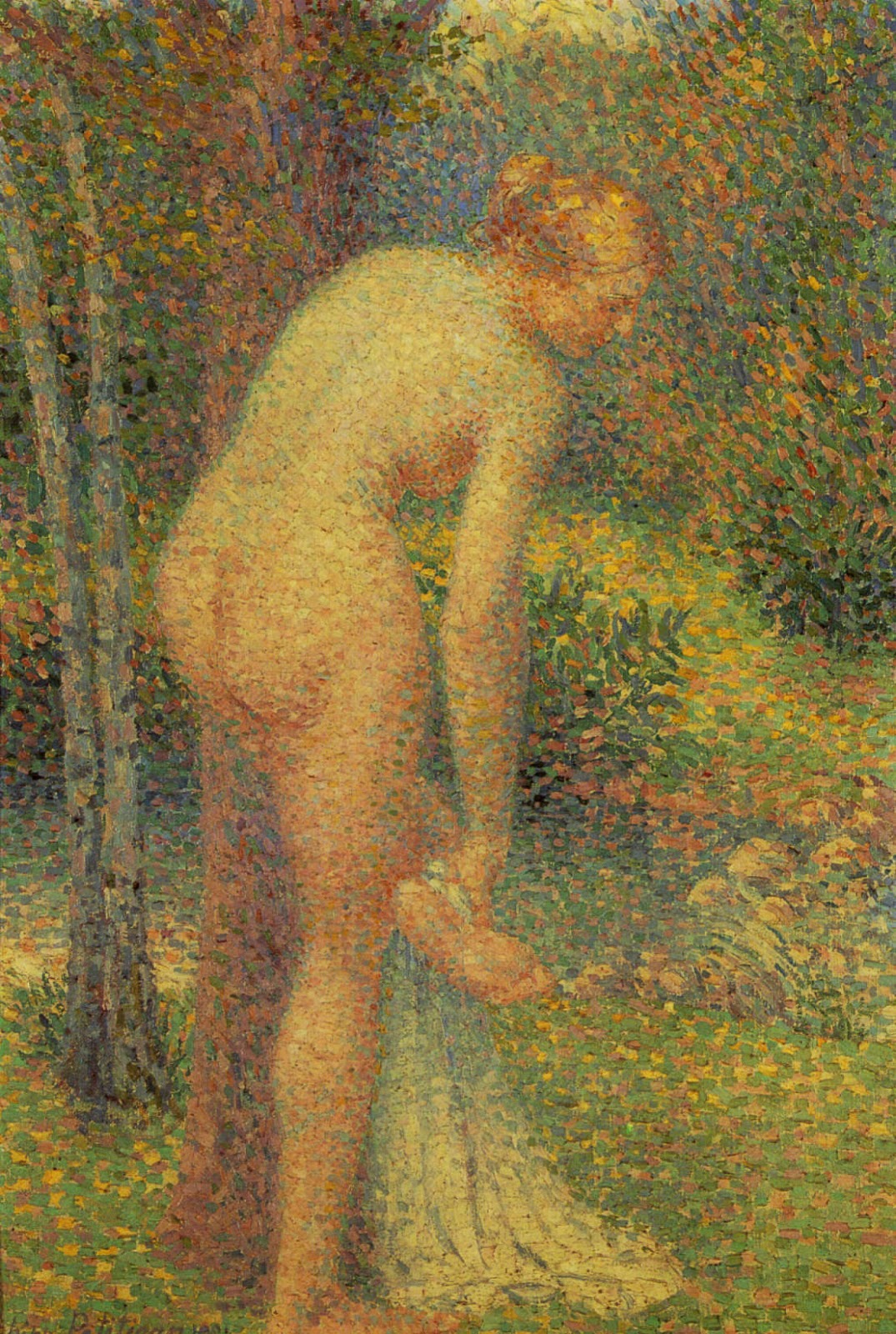

Though the work below looks like it belongs in last week's blog post on Impressionism, given it's strong featuring of patches of light, 'Baigneuse' by Hippolyte Petitjean was actually produced later, in 1921. The work is opalescent, and while the female nude is indeed the 'subject' of the painting, she is perhaps overpowered by the unabashed presence of light. Clarity has been sacrified for an overall atmosphere of warmth. With her idealized form (large rump, slim waist, flawless skin), this female nude is reminiscient of classical iterations of female anatomy.

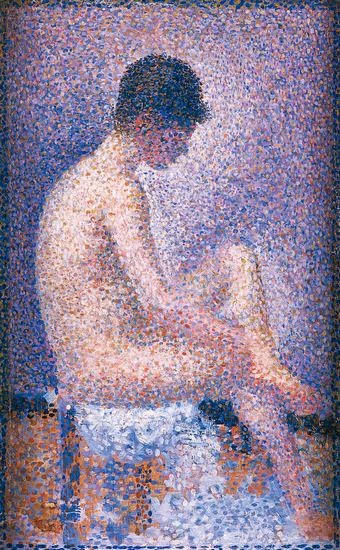

I'll end this blogpost with two works created by George Seurat, a post-impressionist who really spearheaded this new artistic direction. First is 'Poseuse de Profil,' a 1887 work featuring a vague female form. Seurat has abandoned clarity to play with ocular effects and experiement with his technical virtuosity. In prior artistic movements,the artist's ability to realistically and accurately depict the human form was the most greatly valued skill of all. Now, the artist is most valued for his (or her, but we sure are lacking on the XX chromosomes among this crowd) ability to filter and process a scene in a visually interesting way.

Below is a final piece by Seurat —'Cirque' — which he painted in 1891. I end with this piece because it underlines how far artists have moved from the accurate depiction of human anatomy. In this work the human figures are characterized and cartoonish. The central female figure features an exaggerated waste, oversimplified leg muscles, an elongated neck and slim limbs. Her entire anatomy is a sort of calculated spectacle (in line with the subject matter of the work) rather than a faithful depiction of her realistic form. It seems as though Seurat produced this work from his imagination, or at least a photograph, rather than from direct observation — a distinct step away from the 'in situ' style of the impressionists. Cleary, the art world has changed it's relationship with human anatomy, and is quickly moving in a new direction. We'll see where this takes us next week!

No comments:

Post a Comment