Friday, February 28, 2014

Tuesday, February 25, 2014

Quote: the artist's role

"An artist should be something of a geologist to paint rocky scenes correctly, as he should be a botanist to paint flowers, and an anatomist to paint the human form"

-from The Art of Anatomy (67) by B. Rifkin, M. Ackerman and J. Folkenberg

-from The Art of Anatomy (67) by B. Rifkin, M. Ackerman and J. Folkenberg

Art Embodied: anatomical drawing 2

| charcoal, 16.5" x 23.5" |

This charcoal drawing is the second of six anatomical

drawings I will create for my independent study project ‘Art Embodied,’

exploring representations of the human figure throughout history. This piece, Christ in Seven Panels, is based off my

last two weeks of study examining the Medieval and Early Renaissance, with

particular regard to the medieval age.

Each of the seven panels depicts a major event in the life

of Christ, beginning on the top left with his birth and continuing with his

baptism, the first miracle, the raising of Lazarus, the last supper, the

crucifixion, and the ascension. This paneled format was inspired by the

narrative and allegorical nature of medieval art.

In line with the pedagogical role and religious agenda of

the bulk of medieval art, this piece’s conceptual value carries more punch than

it’s aesthetic value. Scale was not used to show perspective but was rather

employed to delineate the importance of the respective figures. Ignoring

anatomical detail, I chose to represent the human forms as crosses for several

reasons. First, in alignment with the simplification of human figures in

medieval art, the cross shape resembles a very simplified human form. Second, the

symbol of the cross epitomizes the idea of iconography, an undercurrent in much

medieval art. Oftentimes figures functioned as symbolic placeholders, heavily

stylized and depicted to tell a story, as opposed to functioning as faithful

representations of the human form.

Monday, February 24, 2014

Art Embodied: Early Renaissance

This past week I have studied the first half of the Renaissance, focusing my energy on art of the 14th and 15th centuries. I have visited the Louvre to get up close and personal with some 15th century art. The book Human Anatomy: A Visual History from the Renaissance to the Digital Age by Benjamin Rifkin, has been an excellent resource for gaining exposure to historical anatomical drawings and understanding the gradual development of anatomy as a scientific and artistic discipline. I look forward to diving into more literature on the Renaissance, and focusing on the later half of the movement as it morphed into Mannerism, this upcoming week.

The study of anatomy came to a standstill during the Medieval age. The physical body carried sinful connotations and dissecting god's creation was strictly forbidden. The stifling of realistic depiction in favor of iconographic art is a phenomenon evident in art created during this time, such as Croix Peinte, painted around 1270 by an Ombrian artist for the Santa Maria Eglise in Assise. Bodily proportion is used haphazardly while scale is employed to indicate the importance of the various figures. Most bodies are draped in layers of clothing, while little to no attention is paid to depicting Christ's anatomy realistically.

Things changed in the 1300s, when master Italian fresco painters such as Giotto and Cimabue created frescos in churches that displayed greater naturalism in figure and gesture. This tendency toward greater realism and depiction of depth launched a rich movement of artistic creation, a 'rebirth' of classical learning, humanistic endeavors, and realistic depiction. During this era the human figure ceased to be a symbolic placeholder and once again took the stage as the celebratory focal point in works. Renaissance artists essentially 're-embodied' art.

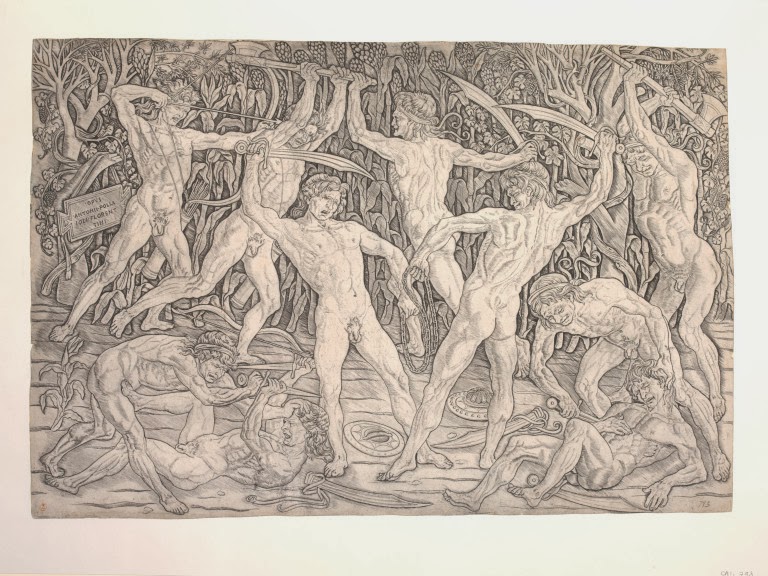

This drastic shift in artistic representation of the human form parallels another rebirth. Anatomy, a field of study lain dormant since the age of the Romans, reemerged, and would remain a scientific and artistic discipline for the rest of time. Mondino da Luzzi, an Italian anatomist known as Mundinus, began to dissect cadavers, energizing the dormant field of anatomical study. Classical ideas of human body and soul as distinct entities found firm footing in 15th century Florence. These Platonic ideologies emphasized the physical body as an essential entity in and of itself. But artists seeking to illustrate and celebrate the human body in all its complicated realistic glory needed more information. Free from the vice-like grip of the church and hungry for anatomical information, artists sought out cadavers themselves and delved into studying the human body. This renewed interest in the physical body is illustrated by detailed carnal engravings such as Battle of Ten Nude Warriors (1472), shown below.

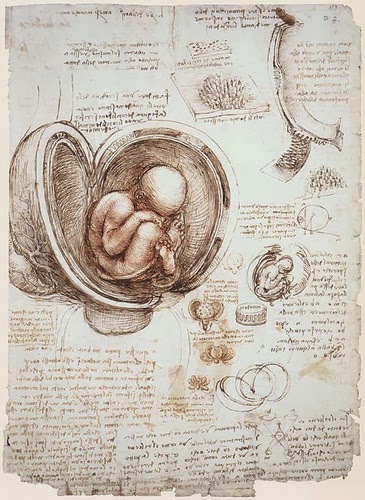

During this time in history, anatomy was a field shared by artists and medical practitioners. Leonardo Da Vinci, a man who bridged both worlds, produced a number of anatomical sketches in the 1400s in preparation for The Last Supper. Da Vinci dissected many cadavers and filled sketchbooks with accurate cross-hatched anatomical depictions.

While the piece below could be interpreted as just one more iconographic image of the Virgin Mary and child, it stands apart from Medieval Art because of increased depth and the naturalness of the figures' gestures. These elements are evidence of a greater attunement to human form on the part of the Renaissance-era artist.

Also hanging at the Louvre and evocative of increasing anatomical insight is L'Alluno, painted by Niccolo di Liberatore for the Chapel of Saint Nicolas de Bari in Ombria in 1492. Though the muscles of the calves and abdomens are clearly simplified and exaggerated, the artist notates the various muscles of the abdomen and limbs with shading rather than the cartoonish lines of the previous century, such as the first painting in this post. Greater depth, depiction of volume, and naturalism in figure and posture emerged as common goals among Renaissance artists.

The study of anatomy came to a standstill during the Medieval age. The physical body carried sinful connotations and dissecting god's creation was strictly forbidden. The stifling of realistic depiction in favor of iconographic art is a phenomenon evident in art created during this time, such as Croix Peinte, painted around 1270 by an Ombrian artist for the Santa Maria Eglise in Assise. Bodily proportion is used haphazardly while scale is employed to indicate the importance of the various figures. Most bodies are draped in layers of clothing, while little to no attention is paid to depicting Christ's anatomy realistically.

Things changed in the 1300s, when master Italian fresco painters such as Giotto and Cimabue created frescos in churches that displayed greater naturalism in figure and gesture. This tendency toward greater realism and depiction of depth launched a rich movement of artistic creation, a 'rebirth' of classical learning, humanistic endeavors, and realistic depiction. During this era the human figure ceased to be a symbolic placeholder and once again took the stage as the celebratory focal point in works. Renaissance artists essentially 're-embodied' art.

This drastic shift in artistic representation of the human form parallels another rebirth. Anatomy, a field of study lain dormant since the age of the Romans, reemerged, and would remain a scientific and artistic discipline for the rest of time. Mondino da Luzzi, an Italian anatomist known as Mundinus, began to dissect cadavers, energizing the dormant field of anatomical study. Classical ideas of human body and soul as distinct entities found firm footing in 15th century Florence. These Platonic ideologies emphasized the physical body as an essential entity in and of itself. But artists seeking to illustrate and celebrate the human body in all its complicated realistic glory needed more information. Free from the vice-like grip of the church and hungry for anatomical information, artists sought out cadavers themselves and delved into studying the human body. This renewed interest in the physical body is illustrated by detailed carnal engravings such as Battle of Ten Nude Warriors (1472), shown below.

During this time in history, anatomy was a field shared by artists and medical practitioners. Leonardo Da Vinci, a man who bridged both worlds, produced a number of anatomical sketches in the 1400s in preparation for The Last Supper. Da Vinci dissected many cadavers and filled sketchbooks with accurate cross-hatched anatomical depictions.

In Venice in 1492 the Gregoriis brothers discovered a series of woodcuts with anatomical diagrams created by a dead physician named Johannes de Ketam. With an upper-class coffee-table market in mind, the brothers published the diagrams, along with an anatomical text written by Mundinus the Italian anatomist, in 1493. Fasciculo de Medicina was immensely popular and opened the floodgates of illustrated anatomical texts that motivated accurate figure drawing throughout the 1500s and 1600s.

This increased interest in anatomy and realistic depiction during the 1400s is reflected in much of the art I saw hanging in the Louvre collections this week. The piece below is a good work to illustrate the slow transition from Medieval to Renaissance art because it features simplified, iconographic elements alongside more nuanced forms. Many of the human figures are planar, frontal and stiff, hallmarks of Medieval Art. Yet the red figure on the right wielding a sword has a more naturalistic pose and indicates the artists interest in experimenting with movement of the human form.

While the piece below could be interpreted as just one more iconographic image of the Virgin Mary and child, it stands apart from Medieval Art because of increased depth and the naturalness of the figures' gestures. These elements are evidence of a greater attunement to human form on the part of the Renaissance-era artist.

Saint Jerome soutenant deux jeunes pendus, painted by Piterro Vannucci around 1473-1475, is equally illustrative of a greater attentiveness to the physical human body. Depicted in death, the two idealized nude figures sport exaggerated muscles and carefully rendered tendons in the neck and feet. While the proportions are not perfectly accurate, the artist clearly sought to illustrate elements of surface anatomy.

Also hanging at the Louvre and evocative of increasing anatomical insight is L'Alluno, painted by Niccolo di Liberatore for the Chapel of Saint Nicolas de Bari in Ombria in 1492. Though the muscles of the calves and abdomens are clearly simplified and exaggerated, the artist notates the various muscles of the abdomen and limbs with shading rather than the cartoonish lines of the previous century, such as the first painting in this post. Greater depth, depiction of volume, and naturalism in figure and posture emerged as common goals among Renaissance artists.

Apollon et Marsyas, painted by Petro de Cristoforo Vannucci around 1495, illustrates the 'rebirth' of classicism during the Renaissance and the 'rebirth' of the human form in all its anatomical glory. This piece epitomizes many themes found in early Renaissance art — the return of the nude human form as subject, realistic depiction mixed with a strong dose of idealism, and naturalism of form as artists strove for anatomical accuracy. During this time artists and medical practitioners were equally dedicated to the frontier of anatomical study, and this commitment is evident in both the anatomically-minded artworks and dissection-based literature published during the Early Renaissance.

This post marks the end of my fourth week of study for my independent project 'Art Embodied'. Keep an eye out for anatomical drawing 2, inspired by the Medieval and Early Renaissance eras, coming soon!

Sunday, February 23, 2014

Art Embodied: selection from 'The Art of Anatomy'

"The body was never a free gift; it gives temporary shelter to our aspirations on a finite lease. We try to preserve and commemorate its tenure. In our age of increasingly narrow technology, we still begin with the body, the province of schools of art and schools of medicine, heirs to our first struggles against mortal limits. These schools cloister optimism. Medical students press through the aromatics of bioled linen, disinfectant, and formaldehyde, making the rounds of formal lectures, half-draped patients, and stripped cadavers. They study the body to improve its fate. Art students, half-nourished by a miasma of primed linen, turpentine, and chalk, study the undraped model in life class, practice the diagrams of geometric perspective, and memorize the skeleton and muscles in anatomy. Some may yet learn to convey ideas as convincing images for the empathetic response of an audience. With kindred presumptions of benefice, the doctor studies the body to improve its fate; the artist to improve its spirit."

-from The Art of Anatomy by Benjamin A. Rifkin

-from The Art of Anatomy by Benjamin A. Rifkin

Art Embodied: Medieval Era

For my independent study project 'Art Embodied' I have been studying the art of the Medieval Era last week. I visited the Cluny Museum of the Middle Ages in downtown Paris to get up close and personal with some Dark Ages art — a rather austere and religiously-themed body of work I am not naturally drawn to. After the glorified idealized bodies of Roman Empire art, it has been interesting to study a time period in which the pedagogical potential of art was emphasized over the aesthetic potential. This past week of study has revealed a stark transition when it comes to depictions of the human figure in Roman and Medieval Art. To start off, check out these figures in the stained glass windows of the Cluny museum — simplified and planar, they border on caricature.

With the fall of the Roman Empire in 500 A.D., the artistic goals of realistic depiction of the human figure, illusion of depth and idealization of the human form went to the wayside. The western half of the Roman empire broke into a variety of disorganized, impoverished kingdoms, while the eastern half morphed into a surviving power called the Byzantine Empire. Medieval art, created from 500 to 1500 A.D., straddles several eras: the Dark Ages from 500-1000 A.D., the Romanesque era from 1000-1200, and the Gothic era from 1200 to 1500. During this time art diverged strongly from the style of the Roman Empire.

With the fall of the Roman Empire in 500 A.D., the artistic goals of realistic depiction of the human figure, illusion of depth and idealization of the human form went to the wayside. The western half of the Roman empire broke into a variety of disorganized, impoverished kingdoms, while the eastern half morphed into a surviving power called the Byzantine Empire. Medieval art, created from 500 to 1500 A.D., straddles several eras: the Dark Ages from 500-1000 A.D., the Romanesque era from 1000-1200, and the Gothic era from 1200 to 1500. During this time art diverged strongly from the style of the Roman Empire.

Filling the power vacuum created by the fall of the Roman Empire, Christianity spread through Europe during the Medieval Era and drastically affected the content and style of the art. In Roman art human figures had served as the embodiments of religious figures and celebrated the idealized human form. This approach would no longer fly in post-Roman Europe, where Christian doctrine forbid creating realistic imagery. In Exodus 20:4 God tells Moses the Israelites should not make 'any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.' In addition, prominent Christian theologians in post-Roman Empire Europe, such as St. Augustine of Hippo, were calling realistic imagery a sin. According to St. Augustine's writings, realistic art is a lie — an attempt at truth when it is in fact not reality. This anti-realism campaign among Christian theologians may have been energized by the idea that the production of realistic images would lead to idolatry.

These ideas had powerful ramifications on art created during the Medieval Era. Art retained a place in churches as a powerful way to disseminated religious ideas and color religious rituals. But the idea that realistic imagery walked the tightrope of idolatry motivated Medieval artists to steer clear of realistic depictions and opt for stylized iconographic images more in line with Christian theology. During this time sculpture became less popular while mosaic flourished in the Byzantine empire, mural painting boomed, and illumination —the art of illustrating manuscripts — was born.

As illustrated by the image of Christ above, stylization was the name of the game during the Medieval Era. This was in sharp contrast to the goals of three-dimensionality and realistic movement evident in Roman-era art. Human figures produced during this time, largely under the umbrella of the Byzantine Empire, are planar and static. For example, in this stone carving scale was used to denote symbolic importance of the various characters, rather than to depict the scene in a realistic way. The tiny servant figure in the front left is clearly a nobody compared to the Virgin Mary and Jesus, as the stilted perspective indicates.

In the less-unified eastern half of the old Roman Empire the aesthetic was less unified, but stylization of figures and religious themes are strong undercurrents in many works. The famous Book of Kells was published during this time, shunning realism for planar, stylized figures and displaying intricate patterns over human subject matter.

As illustrated by the image of Christ above, stylization was the name of the game during the Medieval Era. This was in sharp contrast to the goals of three-dimensionality and realistic movement evident in Roman-era art. Human figures produced during this time, largely under the umbrella of the Byzantine Empire, are planar and static. For example, in this stone carving scale was used to denote symbolic importance of the various characters, rather than to depict the scene in a realistic way. The tiny servant figure in the front left is clearly a nobody compared to the Virgin Mary and Jesus, as the stilted perspective indicates.

In the less-unified eastern half of the old Roman Empire the aesthetic was less unified, but stylization of figures and religious themes are strong undercurrents in many works. The famous Book of Kells was published during this time, shunning realism for planar, stylized figures and displaying intricate patterns over human subject matter.

While decorative patterns temporarily dominated the art scene, the human figure returned as a popular artistic subject matter in 750 A.D. Around the year 1000 A.D. the diverse aesthetic of post-Roman Empire European art began to reunify around the 'Romanesque' style, featuring saturated colors and more naturalistic depictions of the human form.

Several hundred years later in 1200 A.D., European art entered the Gothic Age. Functioning as the bridge between the highly-stylized art of the Dark Ages and the dawn of the Renaissance in Italy, Gothic Art features the reemergence of realism as an aesthetic value. Gothic paintings display the development of perspective along with the naturalization of postures and increased representation of depth. Large wall paintings known as frescos became a popular form of art during this time. Giotto di Bondone, an Italian fresco painter who focused on depicting realistic three-dimensional human forms, is one of many influential artists who spearheaded the transition from Medieval to Renaissance art. The statue, 'Adam', below, was made around 1260 A.D. to be placed in the south transept of Notre Dame. With the natural gesture of the right arm, the nuanced stance of the figure and the subtle depiction of abdomen muscles, the statues is representative of the gradual transition toward naturalism that occurred during the Gothic era.

Artwork made during the Medieval Era functioned as a valuable tool for a motivated and powerful religious agenda. The goal was to employ art as an aesthetic tool to embellish churches, but also to engage it as a pedagogical tool to relay religious stories and dogmas to churchgoers. The carnal body was dismissed as sinful and hidden under layers of drapery, such as in the stained glass figure below. Realistic depiction of the human figure coupled with a strong dose of idealism evident in Roman art gave way to simplification of the human form and abandonment of perspective during Medieval times. With religious institutions condemning imagery and interpreting the physical body as inherently sinful, this may have been the era when art was the least 'embodied' of all.

Several hundred years later in 1200 A.D., European art entered the Gothic Age. Functioning as the bridge between the highly-stylized art of the Dark Ages and the dawn of the Renaissance in Italy, Gothic Art features the reemergence of realism as an aesthetic value. Gothic paintings display the development of perspective along with the naturalization of postures and increased representation of depth. Large wall paintings known as frescos became a popular form of art during this time. Giotto di Bondone, an Italian fresco painter who focused on depicting realistic three-dimensional human forms, is one of many influential artists who spearheaded the transition from Medieval to Renaissance art. The statue, 'Adam', below, was made around 1260 A.D. to be placed in the south transept of Notre Dame. With the natural gesture of the right arm, the nuanced stance of the figure and the subtle depiction of abdomen muscles, the statues is representative of the gradual transition toward naturalism that occurred during the Gothic era.

Artwork made during the Medieval Era functioned as a valuable tool for a motivated and powerful religious agenda. The goal was to employ art as an aesthetic tool to embellish churches, but also to engage it as a pedagogical tool to relay religious stories and dogmas to churchgoers. The carnal body was dismissed as sinful and hidden under layers of drapery, such as in the stained glass figure below. Realistic depiction of the human figure coupled with a strong dose of idealism evident in Roman art gave way to simplification of the human form and abandonment of perspective during Medieval times. With religious institutions condemning imagery and interpreting the physical body as inherently sinful, this may have been the era when art was the least 'embodied' of all.

Tuesday, February 18, 2014

Art girl gets hitched over a pile of zucchini

"You are my wife," said the zucchini man as he passed me a zucchini last Sunday at the weekly outdoor market.

And like that, I found my husband. Or rather, he found me.

Stunned, I turned away from the vegetable stand and be-lined for Cheese Woman. Decked out in a silver bun and smelling of well-aged Roquefort, I figured the flirting potential between the two of us was moderate to low. I needed to clear my head.

After ordering a massive hunk of Camembert and a brick of parmesan (perhaps overkill, but when in France) I realized I was still clenching the zucchini in my left hand. I unzipped my grocery sack, and deftly chucked the zucchini into its bowels. With equal finesse I then proceeded to pay cheese lady with an English five pound note, drop my wallet and spill my sack of tangerines.

"Ce sont pas euros," Cheese Lady stated in a matter-of-fact-I-eat-Brie-like-it's-my-job sort of voice as I lunged for my wallet and watched my oranges disperse to every corner of the market. Durn.

The thing is, I'm not ready to be a wife. I'm not prepared to commit to a life as Mrs. Zucchini Man, whipping out zucchini pancakes every morning, blending zucchini smoothies around midday and baking up zucchini casseroles every night before I crawl between zucchini-printed sheets on a humble yet well-kept zucchini farm. I'm twenty years old for crying out loud.

Courgette is the french word for zucchini. I learned this from my future husband, when I first ambled up to his stand.

"Bonjour," I'd said.

"Where are you from?" he'd asked. Ugh. I hate that after two syllables frenchies can tell I'm from Mars. He could have at least waited until I murdered the pronunciation of courgette before he pegged me as a tourist and inquired about my lineage.

"Je suis americaine," I replied. He was tan with dark hair and dark eyes. Almost tall dark and handsome, minus the four inches needed to meet the first qualifier.

"Ah, je suis espanol," he said smiling. "You are here for the week?"

"Non, pour six mois," I said, bursting into a grin. Every time I say that I feel like i'm taking a bath in chocolate syrup. But no time for food metaphors now because here I was with Zucchini Man and I needed to buy a zucchini and — not knowing the word for zucchini — this was going to be a struggle.

"Je voudrais une chose comme un concombre, mais plus dense," I ordered. A dense cucumber, really Phoebs, that's the best you can do?

"Un concombre mais plus dense," Zucchini Man repeated. "Ummmm, ici?"

Bam. Zucchini. Working off the shaky scaffolding of a request for "dense cucumber," Zucchini Man was a telepathic guru. He was already outperforming Garlic Man, who had given me shallots when I'd asked for a petit ongion, which he finally switched out for the garlic after I shook my head and said "non, quelque chose qui a un odeur plus fort," something with a stronger smell. Never before has grocery shopping so closely resembled a round of twenty questions.

"Une courgette," zucchini man said as passed the zuke from one hand to another. "Pour toi" he added as he held up a clementine and passed it to me. It was then that he told me I was his wife. It was then that I'd bolted.

With British Pounds rather than her native Euro currency, Cheese Woman was thoroughly disgruntled. I was equally disgruntled because she had cut me off a slice of artisanal Camembert that probably cost half my inheritance. And I wasn't ready to get married. And my organic tangerines were on the ground.

"Un moment," I told Cheese Woman. She could just let her cheese age for a few minutes while I found an ATM.

Fate is a fickle friend. And she was feeling especially fickle today, as she had placed the ATM directly in front of the zuke stand. I wasn't ready to interact post-proposal. I needed some time to process. Fate wasn't listening. So I got to awkwardly make peripheral eye contact with Zucchini Man, grunt in response when he shouted out "La semaine prochaine!" See you next week!, and smile out of one side of my mouth as I passed the zucchini stand a third time on my way back to the chaste aura of cheese woman's stall.

Switched Cheese Woman out for euros, yanked my shopping bags onto my shoulder, and headed for home to cook up some Sunday lunch. Anything but a zucchini smoothie would hit the spot.

And like that, I found my husband. Or rather, he found me.

Stunned, I turned away from the vegetable stand and be-lined for Cheese Woman. Decked out in a silver bun and smelling of well-aged Roquefort, I figured the flirting potential between the two of us was moderate to low. I needed to clear my head.

After ordering a massive hunk of Camembert and a brick of parmesan (perhaps overkill, but when in France) I realized I was still clenching the zucchini in my left hand. I unzipped my grocery sack, and deftly chucked the zucchini into its bowels. With equal finesse I then proceeded to pay cheese lady with an English five pound note, drop my wallet and spill my sack of tangerines.

"Ce sont pas euros," Cheese Lady stated in a matter-of-fact-I-eat-Brie-like-it's-my-job sort of voice as I lunged for my wallet and watched my oranges disperse to every corner of the market. Durn.

The thing is, I'm not ready to be a wife. I'm not prepared to commit to a life as Mrs. Zucchini Man, whipping out zucchini pancakes every morning, blending zucchini smoothies around midday and baking up zucchini casseroles every night before I crawl between zucchini-printed sheets on a humble yet well-kept zucchini farm. I'm twenty years old for crying out loud.

"Bonjour," I'd said.

"Where are you from?" he'd asked. Ugh. I hate that after two syllables frenchies can tell I'm from Mars. He could have at least waited until I murdered the pronunciation of courgette before he pegged me as a tourist and inquired about my lineage.

"Je suis americaine," I replied. He was tan with dark hair and dark eyes. Almost tall dark and handsome, minus the four inches needed to meet the first qualifier.

"Ah, je suis espanol," he said smiling. "You are here for the week?"

"Non, pour six mois," I said, bursting into a grin. Every time I say that I feel like i'm taking a bath in chocolate syrup. But no time for food metaphors now because here I was with Zucchini Man and I needed to buy a zucchini and — not knowing the word for zucchini — this was going to be a struggle.

"Je voudrais une chose comme un concombre, mais plus dense," I ordered. A dense cucumber, really Phoebs, that's the best you can do?

"Un concombre mais plus dense," Zucchini Man repeated. "Ummmm, ici?"

Bam. Zucchini. Working off the shaky scaffolding of a request for "dense cucumber," Zucchini Man was a telepathic guru. He was already outperforming Garlic Man, who had given me shallots when I'd asked for a petit ongion, which he finally switched out for the garlic after I shook my head and said "non, quelque chose qui a un odeur plus fort," something with a stronger smell. Never before has grocery shopping so closely resembled a round of twenty questions.

"Une courgette," zucchini man said as passed the zuke from one hand to another. "Pour toi" he added as he held up a clementine and passed it to me. It was then that he told me I was his wife. It was then that I'd bolted.

With British Pounds rather than her native Euro currency, Cheese Woman was thoroughly disgruntled. I was equally disgruntled because she had cut me off a slice of artisanal Camembert that probably cost half my inheritance. And I wasn't ready to get married. And my organic tangerines were on the ground.

"Un moment," I told Cheese Woman. She could just let her cheese age for a few minutes while I found an ATM.

Fate is a fickle friend. And she was feeling especially fickle today, as she had placed the ATM directly in front of the zuke stand. I wasn't ready to interact post-proposal. I needed some time to process. Fate wasn't listening. So I got to awkwardly make peripheral eye contact with Zucchini Man, grunt in response when he shouted out "La semaine prochaine!" See you next week!, and smile out of one side of my mouth as I passed the zucchini stand a third time on my way back to the chaste aura of cheese woman's stall.

Switched Cheese Woman out for euros, yanked my shopping bags onto my shoulder, and headed for home to cook up some Sunday lunch. Anything but a zucchini smoothie would hit the spot.

Friday, February 14, 2014

Art Girl dates french man who hasn't heard of the Mona Lisa

The date was going so well.

Until I told him I had been at the Louvre earlier in the day, and had seen the Mona Lisa.

"Qui?" he asked, his tone casual.

"The Mona Lisa," I said. The music in the bar was loud, he probably just hadn't heard me.

"Qui?" he asked again, smiling this time. "C'est un de tes amis?"

I gulped. He'd just asked if the Mona Lisa was one of my friends.

"Non, c'est le Mona Lisa, la peinture." Only the most famous painting of all time...(!!!!). "Tu ne la connait pas?"

"Ummm, Mona Lisa? Non," he said, still smiling.

Deeply concerned. Art Girl does NOT date men who have not heard of the Mona Lisa. And the fact that this guy was French was adding insult to injury. I excused myself to the bathroom, taking my purse, plotting my subtle escape through a sidedoor or backdoor or hell, a trap door.

Peed. Didn't find any doors besides the main door. Returned to date to tell him I really must go. He was looking at his cell phone. You french-poser-head-in-the-clouds-art-ignoramous. I sat down on the stool next to him, ready to bolt.

"La Joconde!" he spouted, eager, holding up a photo of that famous smiling lady on his phone. "Tu parle de la Joconde, mais oui, bien sur je lui connais," he said, chuckling.

I sighed a deep sigh of relief. He did know the Mona Lisa, she just has a different identity on this side of the Atlantic. French boy could order another round.

Until I told him I had been at the Louvre earlier in the day, and had seen the Mona Lisa.

"Qui?" he asked, his tone casual.

"The Mona Lisa," I said. The music in the bar was loud, he probably just hadn't heard me.

"Qui?" he asked again, smiling this time. "C'est un de tes amis?"

I gulped. He'd just asked if the Mona Lisa was one of my friends.

"Non, c'est le Mona Lisa, la peinture." Only the most famous painting of all time...(!!!!). "Tu ne la connait pas?"

"Ummm, Mona Lisa? Non," he said, still smiling.

Deeply concerned. Art Girl does NOT date men who have not heard of the Mona Lisa. And the fact that this guy was French was adding insult to injury. I excused myself to the bathroom, taking my purse, plotting my subtle escape through a sidedoor or backdoor or hell, a trap door.

Peed. Didn't find any doors besides the main door. Returned to date to tell him I really must go. He was looking at his cell phone. You french-poser-head-in-the-clouds-art-ignoramous. I sat down on the stool next to him, ready to bolt.

"La Joconde!" he spouted, eager, holding up a photo of that famous smiling lady on his phone. "Tu parle de la Joconde, mais oui, bien sur je lui connais," he said, chuckling.

I sighed a deep sigh of relief. He did know the Mona Lisa, she just has a different identity on this side of the Atlantic. French boy could order another round.

Art Girl encounters fascist dictator disguised as painting teacher

Every Monday at 5:15 p.m. I lug my bright red portfolio and bulging bag of acrylic paints onto the metro and make my way to the Sorbonne's art building. Forty five minutes later, usually disgruntled and undoubtedly disheveled, I arrive in the painting studio. It's a tall room with unfinished walls, large tables and several sinks. When you enter the room two things will catch your attention right away — the presence of a nude in the corner, posing languidly on one of the painting tables, and the heavy scent of oil paint on oil paint on oil paint. While I am positive the french stance on nudity is more lenient than in America, I am also quite sure their stance on ventilation is equally relaxed.

There are around twelve students in my class, give or take the three breaking for a cigarette in front of the building at any one time. The teacher, Monsieur Dulom, is a man in his fifties, with longish dark brown hair, perfectly round black-framed glasses, and a clinically strong aversion to saying anything positive about any one's art.

In fact, never in my life have I encountered such a critical art teacher. For three hours he holds his hand behinds his back and saunters from one student to the next. The room is silent, but for the quiet swish of brush strokes, and Monsieur Dulom's low voice.

"Degoutant," he says, after looking at my painting for several minutes. "Les coleurs sont degoutant." (Translation: disgusting, your colors are disgusting). He then slips into a five minute description of the problem, gesturing with his arms, weilding grand metaphors. This is where my already lose grasp on understanding french loses complete hold...I watch him with big eyes, follow his hands as he waves them from the ceiling to a particular spot on my painting. His voice rises and falls, he sits, he stands. Then the room falls silent again. "Tu comprends?" he asks."Oui, merci," I say, in fact understanding little except that he is most definitely not pleased. I do however understand what he says to the next student, someone I consider to be cranking out Michelangelo-caliber portraits on a regular basis. "Ah, c'est la merde," Dulom says. This is shit.

The first day of class I was proudly setting out my new french art supplies — a big pad of acrylic paper, large tubes of acrylic paint, my pack of sleek new brushes and a pallet knife — when Monsieur Dulom strutted over.

"Qu'est ce que ce?" he asked as he rubbed a piece of my canvas paper between his two fingers.

"Uhhh...papier?" I replied. He pulled his glasses down to the tip of his noise and peered at me with a look of deep disdain.

"Do you know of any famous artists who painted on canvas paper?" he asked me, in french. I nodded no. "That's because there aren't any," he said. "This may be easy to carry on the subway, but you need to buy better materials, you need canvas." Before he turned he pulled his glasses back up his nose and said "If you don't take yourself seriously, no one else will."

In other words, welcome to painting class.

There are around twelve students in my class, give or take the three breaking for a cigarette in front of the building at any one time. The teacher, Monsieur Dulom, is a man in his fifties, with longish dark brown hair, perfectly round black-framed glasses, and a clinically strong aversion to saying anything positive about any one's art.

In fact, never in my life have I encountered such a critical art teacher. For three hours he holds his hand behinds his back and saunters from one student to the next. The room is silent, but for the quiet swish of brush strokes, and Monsieur Dulom's low voice.

"Degoutant," he says, after looking at my painting for several minutes. "Les coleurs sont degoutant." (Translation: disgusting, your colors are disgusting). He then slips into a five minute description of the problem, gesturing with his arms, weilding grand metaphors. This is where my already lose grasp on understanding french loses complete hold...I watch him with big eyes, follow his hands as he waves them from the ceiling to a particular spot on my painting. His voice rises and falls, he sits, he stands. Then the room falls silent again. "Tu comprends?" he asks."Oui, merci," I say, in fact understanding little except that he is most definitely not pleased. I do however understand what he says to the next student, someone I consider to be cranking out Michelangelo-caliber portraits on a regular basis. "Ah, c'est la merde," Dulom says. This is shit.

The first day of class I was proudly setting out my new french art supplies — a big pad of acrylic paper, large tubes of acrylic paint, my pack of sleek new brushes and a pallet knife — when Monsieur Dulom strutted over.

"Qu'est ce que ce?" he asked as he rubbed a piece of my canvas paper between his two fingers.

"Uhhh...papier?" I replied. He pulled his glasses down to the tip of his noise and peered at me with a look of deep disdain.

"Do you know of any famous artists who painted on canvas paper?" he asked me, in french. I nodded no. "That's because there aren't any," he said. "This may be easy to carry on the subway, but you need to buy better materials, you need canvas." Before he turned he pulled his glasses back up his nose and said "If you don't take yourself seriously, no one else will."

In other words, welcome to painting class.

Art Embodied: anatomical drawing 1

| mixed media, 16.5" x 23.4" |

This anatomical drawing corresponds to my first two weeks of study focusing on the eras of the Ancient Egyptians and Classical Antiquity.

I decided to focus on the Ancient Egyptians, because I had been surprised by the intricacy of their anatomical understanding, and their singular yet logical way of explaining how the body works. The inspiration for this piece comes from the Ebers Papyrus, one of the main Ancient Egyptian medical papyrus scrolls written around 1500 B.C. The 110 page scroll contains medical remedies, as well as explanations of select aspects of human anatomy, such as the "Treatise on the Heart" section. Feel free to check out the University of Chicago translation of the papyrus here.

To create this piece I focused on the "Treatise on the Heart" (located in Chapter XX of the translated version). On page 129 the translation reads:

In the Heart are the vessels to the whole of the body...there are four vessels to the nostrils, two of which convey mucus and two blood. There are four vessels in the inside of either Temple...when the breath goes into the Nose and makes its way to the Heart and Intestines, and the last-named vessels give to the body richly thereof...

Based on this treatise, I created a diagrammatic representation of the human body and its vessels. I used Ancient Egyptian wall drawings as references for the two figures. In the background I recreated some of the heiroglyphs on the actual Ebers Papyrus. The two red hearts are emphasized in the piece, as the Ancient Egyptians believed the heart was not only the "centre of the vessels to all the limbs" but also the source of thoughts and the home of the human soul.

Thursday, February 13, 2014

Art Embodied: classical antiquity

During week two of my independent study project 'Art Embodied' I have been studying the era of classical antiquity. This post focuses on what the Greeks and Romans knew about anatomy, and how this knowledge is illustrated in their depictions of the human figure. First some sketches, from my time spent geeking out in the Louvre this week:

During the time of the Greeks anatomy emerged as a scientific field of study. Herophilus, a Greek anatomist born in 335 BC spearheaded anatomy studies during his time, and is known as the 'Father of Anatomy'. A medical professional himself, Herophilus believed a solid understanding of the human body was of prime importance to Greek society, as illustrated by the quote below.

"Wisdom is indemonstrable, art uncertain, strength powerless, wealth useless and speech impotent if health be absent" —Herophilus

Unfortunately, Herophilus' record is not totally clean, as he has been accused of vivisection (live dissection) of condemned criminals passed on to him by the rulers of Alexandria. Despite this semi-sketchy resume, Herophilus is considered the first to systematically dissect the human body, and the first to perform an autopsy with the goal of learning about disease. Human dissection was regarded as desecration of the human body at the time, so Herophilus' work was considered taboo. In fact, after Herophilus, systematic human dissection largely dissapeared until the 1500s, and did not become a requirement for surgeons-in-training until the 17th century.

Based on dissection, Herophilus laid the foundation for much of our modern understanding of anatomy. His findings included the differentation fo arteries and veins based on the thickness of the vessels and the classification of nerves, blood vessels and tendons. Rejecting the Egyptian theory that the heart was the source of thoughts, and Aristotle's notion that the brain was a 'cooling chamber,' Herophilus identified the brain as the 'seat of intellect'. His work led to the recognition of the existence of nerve impulses, classification of two types of nerves and association of nerve damage with paralysis. To top off his huge contributions to the understanding of the nervous system at the time, Herophilus named facial nerves, distinguished the different ventricles of the brain, and identified the cerebellum and cerebrum as separate entities.

Herophilus' work extended to the digestive and reproductive systems. He identified the uterus, uterine tubes and ovaries in women, the prostrate gland in men, and realized that the testes produced sperm. He was the first to accurately describe the liver, he wrote about the salivary glands, and coined the term 'duodenum' to mean the first portion of the small intestine. Herophilus also parsed out the parts of the eye, uniquely identifying the iris, cornea and retina for the first time in history.

Greek anatomical knowledge was more detailed and classified than the Egyptian's understanding. This increased depth of anatomical insight is illustrated in the way the human figure is depicted in the art of the two cultures. Based on my observations of the Louvre's Greek and Roman collections this week, I have identified several major changes in the way the Greeks represented the human figure in contrast to earlier art: increased realism, increased interest in movement, and greater depiction of depth.

In contrast to the art of earlier cultures, Greek depictions of the human form demonstrate increased realism and accuracy. The Art and Architecture of Ancient Egypt describes pre-Greek art as a "diagram of a thing man knew it to be, not as it appears to the eye under transitory circumstances." Artists of earlier cultures, such as the Ancient Egyptians, indeed observed balance and proportion, but artists of antiquity embraced realism to a new degree. Greek and Roman artists aspired to accuracy and ascribed value to the art's proximity to reality.

The shift from highly stylized figures to increasingly realistic depictions of the human figure occurred in Ancient Greece around 400 to 300 BC. The photograph below features The Bull of Crete found in the Temple of Zeus. The metope, or panel, depicts Hercules fighting the bull of Crete. This piece is illustrative of the transition from stylized to more realistic figures, because the figure of Hercules is loyal to both reality and the idealism of the artist. Some elements of the figure, such as the protruding rib cage and exaggerated muscles, are stylized. The artist took liberty in overemphasizing certain parts of the figure, yet other details, such as the navel, were considered unimportant are are over-simplified in the work. While elements of exaggeration are indeed present, the figure as a whole is quite realistic, and rests on the door step of the true classical period.

In contrast to the static forms of the Egyptians, Greek artists sought to depict the human figure as a dynamic form. This commitment to accurately representing movement is evident in Greek sculptures at the Louvre such as the statue shown below, the Gladiator Borghese. Created in 100 BC from a monolithic piece of marble, this statue illustrates the Greeks' increased expressiveness in depicting the human form. The work has elements of exaggeration, such as the emphasized torso muscles, but the artist's underlying goal of representing this male body as it appears to the eye is evident.

In addition to representing movement of the human body more accurately, classical artists also began to experiment with different types of movement. For example, in the Roman stuate Hermaphrodite Endormi, the soft and realistic figure is shown contorted in sleep, wracked by a troublesome dream.

Similarly, in the Torment of Marsyas, a Greek sculpture from the Hellenistic period recreated by Roman artists around 100 AD, the figure hangs with it's sides protruding and muscles stretched — a bizarre position the likes of which are not observed in pre-antiquity art.

Finally, in contrast to the planar nature of the Ancient Egyptian figures I studied last week, it seems Greek artists took greater pains to suggest depth in their work. During the classical era, muscles emerged as a prominent element in artistic representations of the human figure. Based on the complexity of the surface of sculptures such as the one below, many artists of antiquity sought to faithfully depict the myriad contours of the human body.

In summary, human dissection led to the emergence of anatomy as a field of study during the classical era. Increased understanding of the structure of the human body is illustrated by the human figures present in Greek and Roman art. In contrast to human bodies in art from previous eras, these figures are increasingly realistic, more dynamic, and present a stronger illusion of depth.

As this post marks the end of week two of my independent study project, it is now time for me to create an anatomical drawing based on the last two weeks of study.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)